We went to the university this morning at 7:45 a.m. as usual. The streets of Kabul were busy like they normally are in the early morning. A few hours into our lecture, I received a phone call from our office manager, Daud, telling me that there was another suicide attack in the center of the city. This time it was the deadliest attack since the Taliban regime was toppled in 2001, killing 35 people from the local police academy and injuring over 50 others. The bus that carried the academy's instructors and students was set ablaze during the rush hour at around 8:10 a.m.

I noticed a little commotion among our students as some of them received SMS messages from worried parents and others who heard the news. I saw many concerned faces in our classroom, including our interpreter, Dr. Jawad, who seemed unusually restless. During the morning tea break, some students came up to me to talk about what happened as if they just wanted someone from a foreign country to listen to them. Ramin and Akbar told me that they were uncertain about the future of their country. I saw both anxiety and frustration in their eyes as they described how neighboring countries and individual groups create instability within Afghanistan. I felt like that they were especially frustrated because of their inability to stop the violence and chaos that have become part of their daily life. By the end of our conversation, I found out that both Ramin and Akbar lost two of their friends in today's bomb explosion on the bus. When Akbar said that he would be the next victim of an explosion, I attempted to give him some reassurance by telling him that things were going to improve.

Stories like these are not uncommon in Afghanistan. Many families have had losses, and almost everyone has been at least internally displaced or has lived as a refugee in Iran or Pakistan. While millions still live in neighboring countries, thousands have returned to start anew. Many who returned to the country ended up in Kabul for several reasons. In addition to offering relatively more job opportunities, many believed that Kabul was a safe place in the context of Afghanistan. Unfortunately, it is not the case anymore. Increasingly, Kabul is becoming a battleground for suicide attacks and terror tactics. This uncertainty and instability create a major concern for the future.

Sunday, June 17, 2007

Saturday, June 16, 2007

Day in Kabul

Today was an intense day. It started with an early morning suicide attack in the western part of the city. The bomb targeted the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) led by NATO. In the midst of the incident, however, several civilians were injured and one of them subsequently died. The news reports suggest that the ISAF soldiers opened fire on the Afghan civilians while ISAF claims that there was a "weapon malfunction." Dozens gathered in protest after the shootings of the civilians as incidents like these create much anger among the locals. The morale is already low among the Afghans, and many feel disillusioned by the bleak prospects of a better future.

While the day started with unrest, our students still showed up at 8:30 a.m. and continued to learn about accounting. As strange as it may sound, no one at the university mentioned the early morning suicide attack. Our interpreter, Dr. Jawad, who lives in the western part of Kabul didn't mention anything either. Perhaps he didn't want to talk about it or was unaware of what happened. As usual, however, he did an outstanding job at interpretation. I told him about his engaging style and excellent linguistic skills, and he was especially pleased by my comments.

Besides helping us with interpretation, Dr. Jawad is a pediatrician and works at a local clinic in Kabul. While my workday ends at 4:30 p.m., his lingers until 9 p.m. daily, except for Fridays. He is also an editor of two local newspapers that cover current political and socioeconomic situation in the country. When we talked about persian poetry, I discovered that he is a poet as well. Dr. Jawad amazes me with his unique character and strong personality. I frequently wonder where he derives his energy to smile and joke while having so much on his plate. This young man has certainly made a tremendous commitment to his war devastated country.

While the day started with unrest, our students still showed up at 8:30 a.m. and continued to learn about accounting. As strange as it may sound, no one at the university mentioned the early morning suicide attack. Our interpreter, Dr. Jawad, who lives in the western part of Kabul didn't mention anything either. Perhaps he didn't want to talk about it or was unaware of what happened. As usual, however, he did an outstanding job at interpretation. I told him about his engaging style and excellent linguistic skills, and he was especially pleased by my comments.

Besides helping us with interpretation, Dr. Jawad is a pediatrician and works at a local clinic in Kabul. While my workday ends at 4:30 p.m., his lingers until 9 p.m. daily, except for Fridays. He is also an editor of two local newspapers that cover current political and socioeconomic situation in the country. When we talked about persian poetry, I discovered that he is a poet as well. Dr. Jawad amazes me with his unique character and strong personality. I frequently wonder where he derives his energy to smile and joke while having so much on his plate. This young man has certainly made a tremendous commitment to his war devastated country.

Monday, June 11, 2007

Troubled land

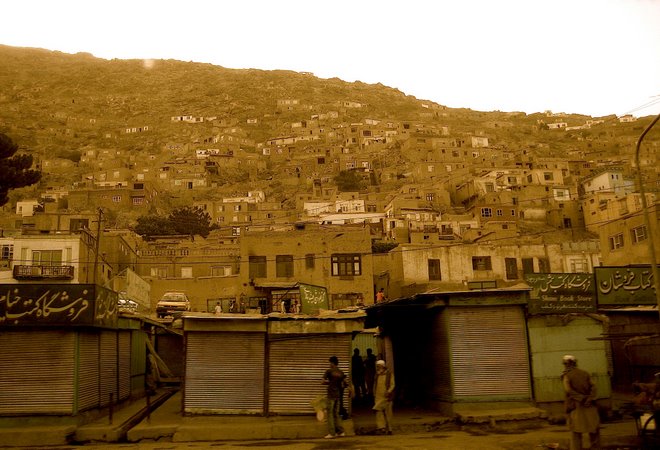

Kabul University is located about twenty minutes away by car in the southern part of the city. As we drove through Kabul in the early morning, I observed people rushing to work and starting their daily activities. I am sure, however, that many of those people never had a chance to work that day as I saw many men lined up in groups waiting for work to come along.

Afghanistan is a hit-or-miss place like many other developing countries. Upon seeing many parts of Kabul, the question that I ask myself, however, is whether the country is truly developing. While exploring the capital, I kept asking Najib, our driver, about the city center. I was hoping to see some kind of a center with buildings in a more or less decent shape. What I saw instead was a city that looked like a giant dusty village with the signs of prolonged war everywhere. There are war-torn buildings, poor roads and chaotic traffic that is navigated by the traffic law enforcement people. With a weary smile on his face, Najib explained to me in Dari that long years of conflict has made Afghanistan "thin."

I saw the worn-out city Najib talked about, and in many ways it reminded me of the images of Berlin in 1945. While Germany was quickly reconstructed after WWII, few Afghans believe that the promises of reconstruction of the Western nations should be taken seriously. They have reasons to be cynical. It's been almost six years now since the U.S. invasion. Just like Afghanistan was abandoned by the West after the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, the hopes of the Afghans again fell short with the invasion of Iraq and the gradual disappearance of the country from the spotlight of the international community.

Many war remnants of Kabul remind me of my youth. I remember clearly how the soldiers of the 40th Soviet Army were seen off to war in Afghanistan. Soon afterwards, the military cargo planes were busy delivering the coffins of young men from this troubled land. My own neighborhood didn't escape the impact of war across the border as a few men I knew were drafted as well. Those who returned were treated as heros only for a short period of time: until the break-up of the Soviet Union. Many of them subsequently felt abandoned by their newly established governments as the Afghan war had become controversial in the post-Soviet times. Those who didn't make it, perhaps never had a chance to realize that they practically fought a futile war. From Mazar-e Sharif to Kandahar, Afghanistan has sucked so many lives in the past several decades, both on the Afghan and the Soviet sides and in the midst of the endless civil war. The country truly has a complex historical legacy.

Afghanistan is a hit-or-miss place like many other developing countries. Upon seeing many parts of Kabul, the question that I ask myself, however, is whether the country is truly developing. While exploring the capital, I kept asking Najib, our driver, about the city center. I was hoping to see some kind of a center with buildings in a more or less decent shape. What I saw instead was a city that looked like a giant dusty village with the signs of prolonged war everywhere. There are war-torn buildings, poor roads and chaotic traffic that is navigated by the traffic law enforcement people. With a weary smile on his face, Najib explained to me in Dari that long years of conflict has made Afghanistan "thin."

I saw the worn-out city Najib talked about, and in many ways it reminded me of the images of Berlin in 1945. While Germany was quickly reconstructed after WWII, few Afghans believe that the promises of reconstruction of the Western nations should be taken seriously. They have reasons to be cynical. It's been almost six years now since the U.S. invasion. Just like Afghanistan was abandoned by the West after the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, the hopes of the Afghans again fell short with the invasion of Iraq and the gradual disappearance of the country from the spotlight of the international community.

Many war remnants of Kabul remind me of my youth. I remember clearly how the soldiers of the 40th Soviet Army were seen off to war in Afghanistan. Soon afterwards, the military cargo planes were busy delivering the coffins of young men from this troubled land. My own neighborhood didn't escape the impact of war across the border as a few men I knew were drafted as well. Those who returned were treated as heros only for a short period of time: until the break-up of the Soviet Union. Many of them subsequently felt abandoned by their newly established governments as the Afghan war had become controversial in the post-Soviet times. Those who didn't make it, perhaps never had a chance to realize that they practically fought a futile war. From Mazar-e Sharif to Kandahar, Afghanistan has sucked so many lives in the past several decades, both on the Afghan and the Soviet sides and in the midst of the endless civil war. The country truly has a complex historical legacy.

Saturday, June 9, 2007

Departure and arrival

I had a mixed feeling while sitting at the Dubai International Airport. On one hand, I was sad that I left Italia. The realization that the year in Bologna was over had made me even more melancholic. On the other hand, however, I was excited to learn about an entirely new culture. After a few hours of delay, they finally called the Kabul flight. With a boarding pass in my hand, I then completely realized that I was going to a country that has received so much negative coverage over the last several decades. My expectations were primarily shaped by the mainstream belief that Afghanistan is a dangerous and hectic place. Having checked into the waiting lounge, I overheard a few european expatriates talking about their previous experiences with the country. I was happy to hear that their stories have not been too bleak. So, boarding the plane, I felt the natural excitement of going to yet another country.

Upon a few hours in the air, we were finally landing at around 8:30 p.m. Whenever I arrive in a new place, my curiosity always leads me to stare outside the window of an airplane to see the surroundings from a low altitude. This time it was different. With almost absolute darkness underneath our plane, I felt for a moment that the plane was landing straight into the ocean. How can it be that a city of almost 3 million residents has almost no lights? Well, I soon discovered that Afghanistan was almost like a different world. After stepping on the ground and especially coming from Dubai, I saw that life has been taken away from the Kabul International Airport. It was dark, and I could barely see a few planes parked in the distance. As ironic as it sounds, the whole place seemed tranquil, and I could perfectly see the stars hanging over me. It was pleasant to feel a cool breeze in the air.

People at the passport control stand didn't ask me a single question. After picking up my luggage, I ended up outside, near the parking lot. The lot was competely lifeless and dark. All the passengers seemed to rush away with people who greeted them or on their own. I attempted to ask a passing lady if she knew where I could make a phone call from a public phone as I expected someone from our office to pick me up. She ignored me as if I tried to sell her hashish. A few munites later, I was happy to spot an old man who held a piece of paper in his hands with my name written on it. As soon as I told him that I was the person he was looking for, he yanked one of my three bags. I let him do it without hesitation as I was quite exhausted. We jumped into his old Toyota and I heard him swear in Dari as he gave some Afghanis to the man standing at the exit of the parking lot if one could call it a parking lot at all.

As we cruised through the city and I saw armed people with Kalashnikovs on virtually every corner, I asked my driver about the security situation. With a smile on his face, he told me that the primary targets are military convoys and high level politicians. He told me that Kabul was safe. When we arrived in our house surrounded by high walls and barbed wire, I was glad to make it in one piece and without hearing any bombings or grenade explosions. I definitely felt, however, that I was in an entirely different environment.

Upon a few hours in the air, we were finally landing at around 8:30 p.m. Whenever I arrive in a new place, my curiosity always leads me to stare outside the window of an airplane to see the surroundings from a low altitude. This time it was different. With almost absolute darkness underneath our plane, I felt for a moment that the plane was landing straight into the ocean. How can it be that a city of almost 3 million residents has almost no lights? Well, I soon discovered that Afghanistan was almost like a different world. After stepping on the ground and especially coming from Dubai, I saw that life has been taken away from the Kabul International Airport. It was dark, and I could barely see a few planes parked in the distance. As ironic as it sounds, the whole place seemed tranquil, and I could perfectly see the stars hanging over me. It was pleasant to feel a cool breeze in the air.

People at the passport control stand didn't ask me a single question. After picking up my luggage, I ended up outside, near the parking lot. The lot was competely lifeless and dark. All the passengers seemed to rush away with people who greeted them or on their own. I attempted to ask a passing lady if she knew where I could make a phone call from a public phone as I expected someone from our office to pick me up. She ignored me as if I tried to sell her hashish. A few munites later, I was happy to spot an old man who held a piece of paper in his hands with my name written on it. As soon as I told him that I was the person he was looking for, he yanked one of my three bags. I let him do it without hesitation as I was quite exhausted. We jumped into his old Toyota and I heard him swear in Dari as he gave some Afghanis to the man standing at the exit of the parking lot if one could call it a parking lot at all.

As we cruised through the city and I saw armed people with Kalashnikovs on virtually every corner, I asked my driver about the security situation. With a smile on his face, he told me that the primary targets are military convoys and high level politicians. He told me that Kabul was safe. When we arrived in our house surrounded by high walls and barbed wire, I was glad to make it in one piece and without hearing any bombings or grenade explosions. I definitely felt, however, that I was in an entirely different environment.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)